NFT Royalties: Where do we go from here?

Is there a way to enforce NFT Royalties, and do we really want to?

Overview

Recently we’ve seen some drama in the NFT royalty space with many market places making royalty fees optional.

The question becomes: could we have seen this coming, and where do we go next?

Context

Some important context is that NFTs have never actually enforced their royalties on chain. To date how it works is that NFT communities would declare their desired royalty fee, and exchanges would choose to deliver on that royalty.

This worked pretty well for a while. In the early days, NFT collections would request relatively small royalties around 2.5%. Then, over the course of the bull market, NFTs began raising their royalties as high as 20% to soak up more revenue. These royalties were crazy high, but people didn’t complain much because the pie was growing and everybody was making money.

When the bull market slowed down, NFT marketplaces began looking for any way they could to get an edge over their competitors. This lead some of them to making previously mandatory royalty fees optional in an attempt to attract traders who would rather not pay the royalty fee. This plan worked well - almost too well. Marketplaces without mandatory royalties began siphoning more and more of the NFT volume from marketplaces with mandatory royalties. The friendly equilibrium of the past was broken, and a race to the bottom had begun.

Soon after, the major marketplace Magic Eden was forced into making their royalties optional too in order to stay competitive. The market pressure had broken them.

From the game theory perspective, we could have seen this coming.

writes about such end game possibilities back in May of 2021:

The Underlying Issue

Quick note: There are debates over whether or not royalties are even net beneficial for NFT communities. In this post we will proceed on the assumption that royalties are something we do want, and propose solutions for enforcing them. We do acknowledge that this assumption isn’t robust, and leave corresponding debates for another post.

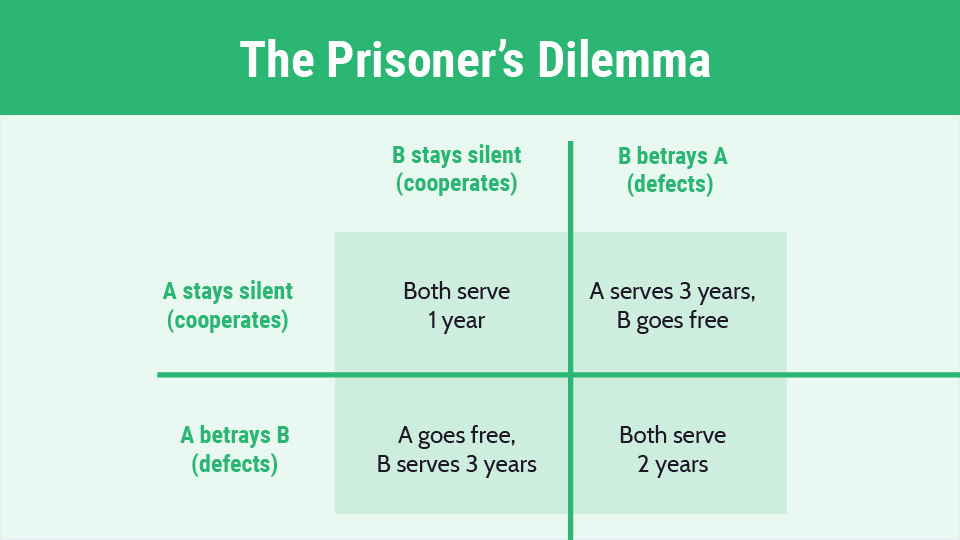

The underlying issue is that marketplaces are presented with a prisoner’s dilemma situation. They can either “cooperate” by continuing to enforce royalties, or “defect” by making them optional and taking market share from cooperative market places.

This puts us in a situation where the ecosystem as a whole is better off if everyone cooperates, but each individual market place is incentivized to defect.

Note, one of the main reasons that marketplaces are even able to defect is that NFT contracts are fully permissionless. This results in a situation where NFT communities have zero leverage over the decisions of marketplaces or what royalties they impose. No matter what a market place does, NFT communities have no way to take action against them in a top down way. The best they can do is kindly request that traders do not use a specific marketplace, but clearly that isn’t working.

Prisoner’s dilemma situations are especially difficult to handle in games which are decentralized or permissionless, but not impossible. The main approaches involve either changing the payout matrix, or turning a one off game into an iterated one. The following is one potential solution to enforcing NFT royalties.

A Potential Solution

First things first, we need to give NFT communities some top down leverage over marketplaces if we want them to have an influence on marketplaces. This means introducing some permissions to NFT smart contracts.

While this may appear to go against Web 3 ethos, remember that the extent to which something is permissionless is a spectrum, not binary. As long as we have a system for holding the NFT contract permissions accountable, we get to keep most of the benefits that come with permissionlessness.

The proposed permissioned NFT contract abides by the following rules (whenever you see a number, that number is configurable to an arbitrary value):

There are three classes of addresses: end users, protocols, and voids.

End user addresses correspond to a real life person who has been verified using a proof of personhood protocol like worldcoin or proof of humanity. End user addresses are permissioned to hold up to 10 NFTs in a collection. It’s necessary that end user addresses correspond to unique people in order to defend against sybil attacks.

Protocol addresses correspond to “friendly” protocols that add value to an NFT community. Protocols validate themselves by staking 10 of the community’s NFTs. Should a protocol behave maliciously, the NFT community can vote to slash the protocols stake. Protocol addresses are permissioned to hold an unlimited number of NFTs in a collection.

Voids addresses are those which aren’t verified as either end users or protocols. They are permissioned to hold up to 0 NFTs in a collection.

End users can transfer NFTs to any verified protocol, but not to other end users or voids. The reason for restricting transfers between end users is that it’s necessary in order to prevent users from using OTC trading to bypass royalties.

Protocols can transfer NFTs to any verified protocol or end user (as long as the end user hasn’t hit their NFT limit), but not to voids.

This set of permissions removes incentives for marketplaces to ignore NFT royalties. Should a protocol behave maliciously, it will be slashed and removed from the list of protocols that are authorized to offer services to an NFT community. This turns the action of “defecting” which previously had a positive EV into one with negative EV.

Unfortunately, non upgradable NFT collections will not be able to add permissions to their existing smart contract without performing a migration, but these types of permissions could be added to any new NFT contract. There are some implementation specifics to work out in more detail, but the general proof of concept has the big working parts.

Generalizing

This post focuses on NFT royalties, but what are the more general concepts at play? I’d say that there are a few main ones:

Blocking protocols which have a net negative effect on an NFT community. NFT marketplaces which don’t enforce royalties are one such example. Others include NFT bribery and vote manipulation protocols.

Restricting users from using their NFTs in ways that have net negative effects on an NFT community. Such use cases are similar to those in the previous point, but facilitated off chain or OTC.

Preventing sybil attacks from negatively affecting NFT communities. You want to avoid cases like whales hoarding large percentages of an NFT collection's supply in ways that limit the number of unique real people who can participate in the community, and casts a cloud over it for fear of the whale dumping their NFTs. In the past we have seen a whale dump their share and tank a community by over 40% in an hour!

This generalization shows that the idea of permissioned NFT contracts are useful for more than just enforcing NFT royalties, and could even be valuable outside the scope of NFTs. The main ideas apply anywhere that you are trying to prevent malicious or mercenary actors from disturbing a pareto efficient situation.

Conclusion

While some find the race to the bottom of NFT royalties on marketplaces disheartening, the least we can do is make the most of it as a data point and wake up call. Going forwards we can look for similar game theoretic predictions, and plan accordingly. As Charlie Munger likes to say, “show me the incentive and i’ll show you the outcome”. In the land of Web 3 we have the ability to manipulate the incentives, and can use this power to improve outcomes.